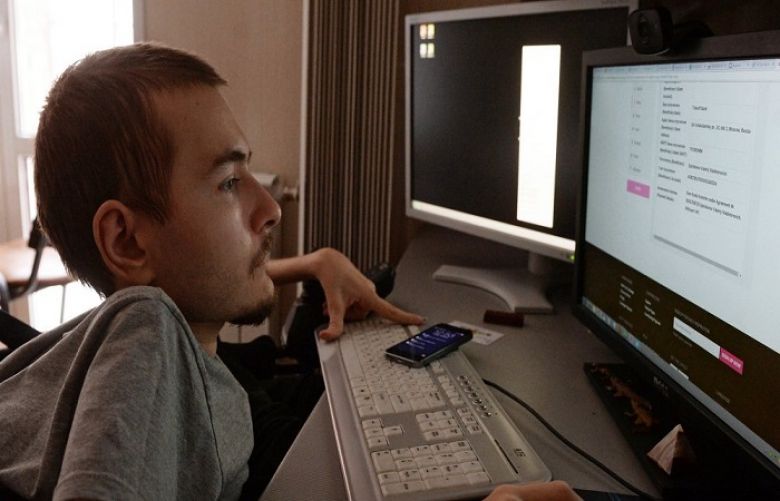

Valery Spiridonov explains why he wants to be the first person to undergo a head transplant, which will be carried out by Italian neurosurgeon Professor Sergio Canavero.

Mr Spiridinov, from Russia, suffers from Werdnig Hoffman disease, a muscle wasting condition that seriously diminishes his physical capabilities and left him dependent on a wheelchair.

Now he has announced his intention to become the world’s first subject of a full head transplant, so that his brain can be attached to a healthy body.

Italian neuroscientist Dr Sergio Canavero claims he can complete the unprecedented procedure in less than a day.

The whole process, Dr Canavero says, is “90 per cent” guaranteed to succeed, though he admitted: “Of course there is a marginal risk. I cannot deny that."

Other doctors have expressed serious doubts, and, in particular, the likelihood that Mr Spiridinov’s brain will still be functional by the time the surgery is complete.

Mr Spiridinov, however, is more optimistic.

“If I have a chance of full body replacement I will get rid of the limits and be more independent”, he said.

Stage one involves cooling the patient and donor’s bodies in order to prevent the brain cells from dying during the operation.

Next, the neck is partially severed and the blood vessels from one body linked to the other with tubes.

Matthew Crocker, consultant neurosurgeon at St George’s Hospital, London, said every section of the operation has a grounding in current science and practice – at least in theory.

“Excluding blood vessels that supply blood to the brain then restoring them with tubes is very well recognised”, he told Sky News.

“Lowering the temperature of the whole body head and brain to between 10 and 20 degrees, usually around 15 to 17 degrees, is a very well recognised technique used for complex neurosurgery or cardiovascular surgery in which there is an expectation that the brain will be starved of its blood and oxygen supply for a substantial period."

Stage two sees the spinal cord cut with an extremely fine blade to minimise damage.

The donor head is then removed, placed on the recipient’s body, and the spinal cord fused back together again using polyethylene glycol, a compound used both in medicine and industrial manufacturing.

Mr Crocker said: “The idea of cutting the spinal cord sharply rather than bluntly has a little medical support. The only well recognised success with spinal cord injury surgery came from a man who had a stab injury rather than a blunt injury."

He added: “I’m sure any of this is really okay, and it requires a little more thought. At what point does one die, might be one for an ethicist to consider.

“But the heart is routinely stopped in open heart surgery, that’s no longer unusual."

Stage three involves knitting together the survivor’s blood vessels and nerves, though Mr Crocker said he doubted whether the feat had ever been attempted on such a scale successfully before.

The body is then kept in a coma for several weeks to prevent movement and allow time for the spinal cord to glue itself back together.

“That is very speculative”, Mr Crocker said.

“The issue here is that someone with a functioning spinal cord is facing having that function completely removed."